The Rules

The summer just after I turned seven, my school bus sideswiped a cyclist.

I was the only one who saw it happen, and up until I wrote that sentence today I have never told anyone. Not a soul.

When it happened my face was pressed to the window as usual, my gaze turned outward to avoid unwanted attention from the crowd of rowdy schoolchildren hemming me in with eyes only for each other as they traded jibes. I never knew what to do with jibes. My vast vocabulary seemed to make things worse, not better. Silence and invisibility was safer. Be boring. Be insignificant.

The bus seemed massive as it drew level with the teenager coasting down the hill on that insignificant framework of metal. I felt the sway as the wheels hit a bump in the roughly sealed road.

The side of the bus slammed into him a few rows in front of my seat. There was no thump, nothing to be heard above the roar of our behemoth's engine, just a streak flying through the air - blue? some yellow maybe? - then the glimpse of a still form sprawled on the brilliant green verge, quickly left behind with the twisted bicycle.

The bus rolled on down the hill, braked, turned the corner.

To speak, to move, was impossible. The movie playing over and over inside my head was hypnotic. Hit. Fly. Still. Hit. Fly Still. I wanted to put the scary story into the box in my head with all the other scary things, but first I had to watch it a thousand times. I knew that because of Rusty. I didn't think about Rusty every day any more. He was in the box with the lid slammed shut. But first, watch the movie a thousand times.

It was just one more situation where I had no idea how to react like other people. Everyone in the whole world seemed to have a rule book for how to behave, but I already knew it was different to mine.

If I was a neurotypical child, clever and observant as I was, surely some part of me would have learned how to behave from what happened to Rusty the year before. In every other respect I was a model child, a people pleaser -

- or rather, an adult pleaser; I still had little idea how to please other children and stop them getting angry with me; they seemed to get upset with me for pleasing the adults, and that was confusing -

- surely some part of me would have known that the right thing was to stand up -

- but no! Sit down while the bus is moving! Don't make adults angry! -

- walk to the front -

- passing those dreadful boys who might - I didn't know what they might do? but I wouldn't like it, I knew that -

- and tell the driver -

- he would feel terrible, and it would be my fault. Don't make adults sad!

Do you see?

I wasn't neurotypical. I was a little girl sitting on the very edge of the autism spectrum, passing easily for 'normal' amongst the adults I was learning to placate, remaining undiagnosed until the age of 63.

(Not like that naked little boy at the bus stop. Now that I know what autism is, I can see that he was right in the heart of ASD Land. His parents must have baulked at putting him in a home, which is what they did back then with children who flouted the Neurotypical Rule Book by such wide margins.)

But still, passing for 'normal' as I did, I couldn't process what had happened quickly enough to act. There was too much noise in my head. Too many contradictions. The logic formed an endless loop.

I was still learning how to pretend, or as they say today in the autism playbook, how to 'mask' my deficits. How to fill the cracks in my social understanding by watching, copying, smiling at the right time. Ignoring how I felt at the right time.

And so, what happened to Rusty, you ask?

Oh, this story needs to come with a trigger warning. If you love animals like I did, like I do, it will kill you.

The year before, when I was just 5 and that same school bus rolled backwards at our bus stop and - right in front of my eyes - crushed the bored neighbourhood kelpie who'd been barking hysterically and snapping at its rear tyres, the younger children had screamed or cried or turned away, and the older children had rushed to tell the adults the news.

"Cec, you ran over Rusty!"

"Who's going to tell Mrs G?"

I'd stood there frozen, watching the dog die gasping and shuddering, his eyes full of raw terror. Silent, my face expressionless, my eyes fixed on the hideous scene playing out before me. Unable to react like other children.

I never told anyone that story either, not till about ten years ago when the box flew open and it slammed into me when I was looking for a hard-hitting story to help me explain to parents that children often don't tell anyone when something traumatic happens to them.

The only sign I ever gave at the time that anything had affected me was when I had a screaming, wailing tantrum the next day as my mother (absent from my side the day before) tried to put me on the school bus as usual. I never had tantrums. I loved going to school, where there were all those adults I could please, all those interesting things to learn and do well for them.

My mother was mystified by this sudden explosion of emotions - today I would call it a meltdown, of course, but they were so rare (because of Rule 1 in my rule book) that I caught her by surprise - but then I regained control (because Rule 1 was the Very First Rule and I'd been practising it a long time), wiped my eyes and stepped calmly onto the bus, so she let it go and never mentioned it again.

Perhaps it was just as well I never told her. She'd seen her own dog run over as a child and never got over it, a story she'd only told me to quiet my endless pleas for a pet of my own. And I always tried to obey that rule book. The first chapter was called 'How to make people like you', with the subheading 'Don't make anyone angry or sad.'

First line, 'Rule 1. Don't upset your mother. Ever.'

So I definitely shouldn't have told her that I'd seen a different movie that morning, a movie that my imaginative, logical, analytical head made up, a movie where that strange little boy who didn't go to school but ran around the neighbourhood naked in the mornings, you know the one? - he ran up and got behind the bus and the bus rolled back and he got squashed on the road and I watched him die, gasping and shuddering, his eyes full of raw terror.

I mean, it was logical. That little boy never followed the rules, just like Rusty. Just like my mother's dog Paddy.

It could have happened.

True confession: I still see movies like that nearly every day of my life. I put two and two together and get a possible disaster. The dog's rope catching around my partner's leg, a fall, his head striking the veranda post. A discarded pair of shoes creating a trip hazard near the stairs. It's a royal pain in the perineum most of the time and irritates the hell out of people who end up on the wrong end of my anxiety, but sometimes my ability to assess risk (some would call it catastrophising) is golden.

The gold? Forty years driving, and I've never had a car accident (I don't count the idiot who rammed me from the back, because there was nothing I could have done to prevent that except for never driving a car). I've learned how to protect myself from danger on the road, because I don't want to be dead, not like Rusty, not like anyone, no way I want to be dead. I've learned to warn others of danger, don't do stupid stuff that might make you dead, just expressed more subtly these days (usually), and I'm gradually learning to let go once I warn them and explain why because otherwise they get shitty with me if I go on and on.

(Which is what my head always says I should do, go on and on till they're not in danger, but sometimes your Aspie head needs to be nudged if you want anyone to love you.)

Best of all, when I'm working with children, I can often anticipate danger and reach out to catch a child before they've even started to fall. And I've learned not to stop them trying stuff. They need to take risks. Just, be there to catch them.

It's like kintsugi, my ability to see risk. It's a little thread of gold given to me by my super-logical, super-analytical Aspie mindset, something to compensate for the cracks in my social skills. So much of my autism is a gift wrapped in awkwardness. I just have to hide my weak points by dressing them up with some pretty, golden glue that other people like, or find useful.

And why did I write this today? Why today, after all those years?

Today I passed a cyclist as I drove home. I gave him a very wide berth, and he waved his thanks. And suddenly the box in my head opened wide and there was that old movie playing in my head, warning me that humans riding on fine webs of metal are fragile, and my superior size didn't give me a right to run him off the road. Pass wide, or slow down till you can. Manage the risk.

Not like that damned school bus.

I was the only one who saw it happen, and up until I wrote that sentence today I have never told anyone. Not a soul.

When it happened my face was pressed to the window as usual, my gaze turned outward to avoid unwanted attention from the crowd of rowdy schoolchildren hemming me in with eyes only for each other as they traded jibes. I never knew what to do with jibes. My vast vocabulary seemed to make things worse, not better. Silence and invisibility was safer. Be boring. Be insignificant.

The bus seemed massive as it drew level with the teenager coasting down the hill on that insignificant framework of metal. I felt the sway as the wheels hit a bump in the roughly sealed road.

The side of the bus slammed into him a few rows in front of my seat. There was no thump, nothing to be heard above the roar of our behemoth's engine, just a streak flying through the air - blue? some yellow maybe? - then the glimpse of a still form sprawled on the brilliant green verge, quickly left behind with the twisted bicycle.

The bus rolled on down the hill, braked, turned the corner.

To speak, to move, was impossible. The movie playing over and over inside my head was hypnotic. Hit. Fly. Still. Hit. Fly Still. I wanted to put the scary story into the box in my head with all the other scary things, but first I had to watch it a thousand times. I knew that because of Rusty. I didn't think about Rusty every day any more. He was in the box with the lid slammed shut. But first, watch the movie a thousand times.

It was just one more situation where I had no idea how to react like other people. Everyone in the whole world seemed to have a rule book for how to behave, but I already knew it was different to mine.

|

| Are there rules for parties? My loathing for them started young. |

If I was a neurotypical child, clever and observant as I was, surely some part of me would have learned how to behave from what happened to Rusty the year before. In every other respect I was a model child, a people pleaser -

- or rather, an adult pleaser; I still had little idea how to please other children and stop them getting angry with me; they seemed to get upset with me for pleasing the adults, and that was confusing -

- surely some part of me would have known that the right thing was to stand up -

- but no! Sit down while the bus is moving! Don't make adults angry! -

- walk to the front -

- passing those dreadful boys who might - I didn't know what they might do? but I wouldn't like it, I knew that -

- and tell the driver -

- he would feel terrible, and it would be my fault. Don't make adults sad!

Do you see?

I wasn't neurotypical. I was a little girl sitting on the very edge of the autism spectrum, passing easily for 'normal' amongst the adults I was learning to placate, remaining undiagnosed until the age of 63.

(Not like that naked little boy at the bus stop. Now that I know what autism is, I can see that he was right in the heart of ASD Land. His parents must have baulked at putting him in a home, which is what they did back then with children who flouted the Neurotypical Rule Book by such wide margins.)

But still, passing for 'normal' as I did, I couldn't process what had happened quickly enough to act. There was too much noise in my head. Too many contradictions. The logic formed an endless loop.

I was still learning how to pretend, or as they say today in the autism playbook, how to 'mask' my deficits. How to fill the cracks in my social understanding by watching, copying, smiling at the right time. Ignoring how I felt at the right time.

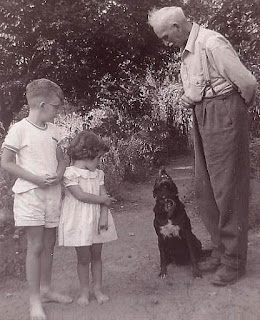

|

| I was a bit afraid of dogs at first... this is Spider, my grandfather's dog. I don't have a photo of Rusty. |

Oh, this story needs to come with a trigger warning. If you love animals like I did, like I do, it will kill you.

The year before, when I was just 5 and that same school bus rolled backwards at our bus stop and - right in front of my eyes - crushed the bored neighbourhood kelpie who'd been barking hysterically and snapping at its rear tyres, the younger children had screamed or cried or turned away, and the older children had rushed to tell the adults the news.

"Cec, you ran over Rusty!"

"Who's going to tell Mrs G?"

I'd stood there frozen, watching the dog die gasping and shuddering, his eyes full of raw terror. Silent, my face expressionless, my eyes fixed on the hideous scene playing out before me. Unable to react like other children.

I never told anyone that story either, not till about ten years ago when the box flew open and it slammed into me when I was looking for a hard-hitting story to help me explain to parents that children often don't tell anyone when something traumatic happens to them.

The only sign I ever gave at the time that anything had affected me was when I had a screaming, wailing tantrum the next day as my mother (absent from my side the day before) tried to put me on the school bus as usual. I never had tantrums. I loved going to school, where there were all those adults I could please, all those interesting things to learn and do well for them.

My mother was mystified by this sudden explosion of emotions - today I would call it a meltdown, of course, but they were so rare (because of Rule 1 in my rule book) that I caught her by surprise - but then I regained control (because Rule 1 was the Very First Rule and I'd been practising it a long time), wiped my eyes and stepped calmly onto the bus, so she let it go and never mentioned it again.

Perhaps it was just as well I never told her. She'd seen her own dog run over as a child and never got over it, a story she'd only told me to quiet my endless pleas for a pet of my own. And I always tried to obey that rule book. The first chapter was called 'How to make people like you', with the subheading 'Don't make anyone angry or sad.'

First line, 'Rule 1. Don't upset your mother. Ever.'

So I definitely shouldn't have told her that I'd seen a different movie that morning, a movie that my imaginative, logical, analytical head made up, a movie where that strange little boy who didn't go to school but ran around the neighbourhood naked in the mornings, you know the one? - he ran up and got behind the bus and the bus rolled back and he got squashed on the road and I watched him die, gasping and shuddering, his eyes full of raw terror.

I mean, it was logical. That little boy never followed the rules, just like Rusty. Just like my mother's dog Paddy.

It could have happened.

|

| Spotting for children risking using the slide a different way. They loved it. |

True confession: I still see movies like that nearly every day of my life. I put two and two together and get a possible disaster. The dog's rope catching around my partner's leg, a fall, his head striking the veranda post. A discarded pair of shoes creating a trip hazard near the stairs. It's a royal pain in the perineum most of the time and irritates the hell out of people who end up on the wrong end of my anxiety, but sometimes my ability to assess risk (some would call it catastrophising) is golden.

The gold? Forty years driving, and I've never had a car accident (I don't count the idiot who rammed me from the back, because there was nothing I could have done to prevent that except for never driving a car). I've learned how to protect myself from danger on the road, because I don't want to be dead, not like Rusty, not like anyone, no way I want to be dead. I've learned to warn others of danger, don't do stupid stuff that might make you dead, just expressed more subtly these days (usually), and I'm gradually learning to let go once I warn them and explain why because otherwise they get shitty with me if I go on and on.

(Which is what my head always says I should do, go on and on till they're not in danger, but sometimes your Aspie head needs to be nudged if you want anyone to love you.)

Best of all, when I'm working with children, I can often anticipate danger and reach out to catch a child before they've even started to fall. And I've learned not to stop them trying stuff. They need to take risks. Just, be there to catch them.

|

| Photo by Freer/Sackler, Smithsonian, via article on kintsugi by Casey Lesser |

It's like kintsugi, my ability to see risk. It's a little thread of gold given to me by my super-logical, super-analytical Aspie mindset, something to compensate for the cracks in my social skills. So much of my autism is a gift wrapped in awkwardness. I just have to hide my weak points by dressing them up with some pretty, golden glue that other people like, or find useful.

And why did I write this today? Why today, after all those years?

Today I passed a cyclist as I drove home. I gave him a very wide berth, and he waved his thanks. And suddenly the box in my head opened wide and there was that old movie playing in my head, warning me that humans riding on fine webs of metal are fragile, and my superior size didn't give me a right to run him off the road. Pass wide, or slow down till you can. Manage the risk.

Not like that damned school bus.

From the scrawny kid in the photo with Candy, Paddy and Vic: I am not a carbon copy of anyone, but my genes are from the same stable as Candy's. Maybe I need to look at my own issues from this perspective. I have wondered, but my readings on the internet (not to be confused with anyone's medical degree) have never suggested that any particular label fitted me neatly. Then again, anyone who fits a label neatly might be a minor character in a very minor novel...

ReplyDeleteHah! Well it’s a spectrum. Neat just doesn’t happen, or it’d be a lot easier for kids to get a diagnosis quickly when they need help. FWIW I reckon the two peas are definitely from the same pod, and remembering Uncle Lloyd’s strange variety of genius merged with social awkwardness, I can guess which side of the family it came from. Perhaps Father Pea’s strange views on company and obsessive nature could be a product of more that war trauma, too.

Delete